THE ESSENTIAL GUIDE TO BAROLO

Barolo is a number of things

Barolo is a village 70 km south of Turin in the Province of Cuneo, in the Region (State) of Piemonte (Piedmont in English and never the hybrid/mongrel Piedmonte!). A beautiful little town, framed by the Castello di Barolo, and small enough to walk fairly thoroughly in under an hour. It contains, just within a couple of hundred metres of each other, the actual cellar doors and wineries of such famous names as Mascarello (Bartolo), Brezza, Borgogno, Barale, Chiara Boschis, Damilano, Marchesi di Barolo and Giuseppe Rinaldi; each of which you can almost stumble upon, such are their (mostly) unprepossessing frontages. The comune’s most famous vineyard Cannubi, itself starts right on the edge of the village.

Barolo village also gives its name to one of the 11 comunes that make up the Barolo wine zone; this is the Barolo DOCG

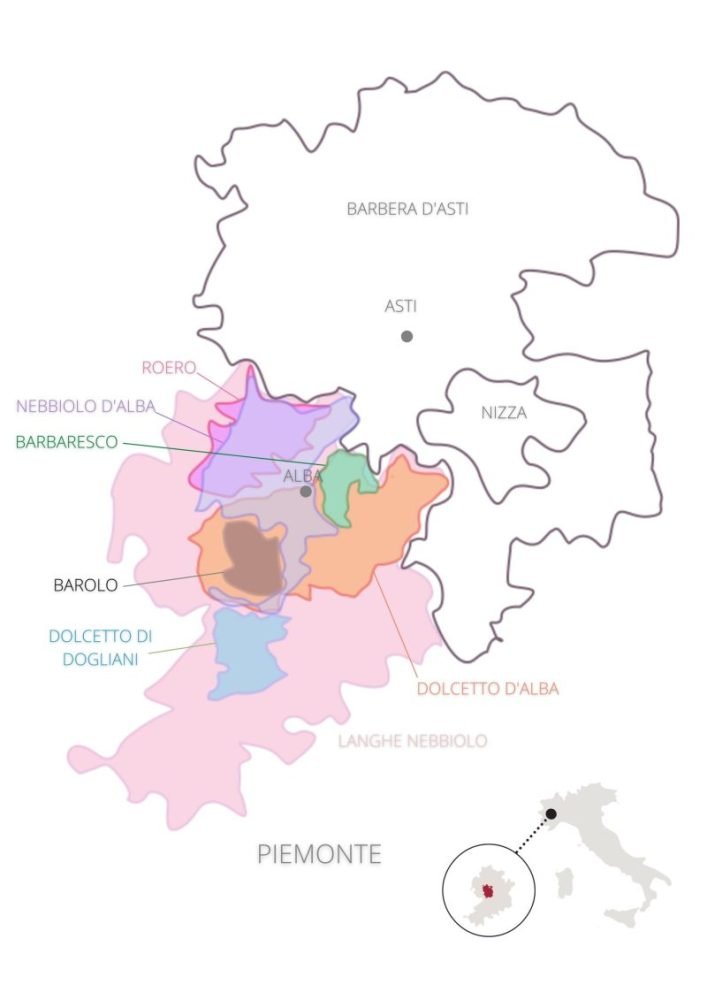

In turn, the wider region known as the Langhe is broadly given the name ‘Barolo’ in common usage. “We had a week in Barolo” may mean we never actually went into the town of Barolo but may have stayed in the general area, even as much as 20km away (from Barolo village itself) and took in some, or many of the delights that characterise the area; be they the Nebbiolo wines actually labelled Barolo or Barbaresco, or the wines named by variety and separate designated zones. Evocative names like Nebbiolo, Barbera or Dolcetto d’Alba, along with the sights like the spectacular views from La Morra or the fabulous food, add up to one great experience. Ah, the food…

In a broader sense, this Barolo area is a concept that stretches even further, taking in a wider area like the Roero zone, famous for its elegant Nebbiolos and, most of all, for Arneis or more north and easterly, to take in the famous Moscato and Barbera d’Asti or the Barbera wines of Nizza and Monferrato, which are growing in repute. Or we might go south of Barolo to Dogliani, the zone which covers many of the best Dolcettos. Each of these basks somewhat in the reflected glory of the Barolo idea.

-

The Barolo appellation or DOCG – Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita – was the inaugural DOC of Italy in 1966 and was one of the first three granted DOCG status. This ‘G’ was added to underline an extra step (over DOC) of the wines needing to pass tasting by a Government-authorised panel, in order to get their numbered DOCG labels to affix to the neck of every bottle.

The DOCG for Barolo requires the following:

100% Nebbiolo grapes

Vineyard altitudes: minimum 170 m, maximum 540 m

Area under vine: just on 2,000 ha

Maximum production per hectare: 54 hL/ha (7,200 bottles)

Ageing is 38 months from 1st November following harvest

Minimum 18 months of that ageing in wood

Riserva can be applied once the wine is aged for 60 months (from 1st November after harvest)

Minimum alcohol: 13% by volume

Minimum total acidity: 4.5 g/L

Minimum dry extract: 22 g/L

Production: up to around 13 million bottles/year. E.g., 972,200 cases were produced in 2018.

-

The 11 comunes that make up the Barolo zone are further identified by 181 MGA’s – Menzione Geografiche Aggiuntive – specific Additional Geographic Mentions. 11 of these are to cover each village or comune and the rest are recognised vineyards – or Cru, if you like. In fact we now commonly use the French term Cru for these individual identified Barolo vineyards. Somewhat similar to the French concept, maybe most similarly to Burgundy, these individual Cru vineyards are often shared by various owners, who may or may not make a wine themselves or sell the grapes. Within these ‘Crus’ there is an allowance for some recognised sub-zones eg Bussia’s Soprana and within them further, some approved sub-plots – similar to a Burgundy lieux dit eg – can be identified on a label, like Cicala, Colonello and Romirasco of Aldo Conterno’s parcels of Bussia Cru of Monforte d’Alba comune. There, that’s not hard to understand…is it?

Barolo is made up of soil that is extremely varied, which justified the work of delineating the broad range of MGAs. This task was completed in 2010, and resulted in 181 names, or MGAs, and among which are 11 villages (or comunes) that can be labelled on wines. They are separate from single-vineyard wines and perhaps best approximate the Villages concept of Burgundy.

NB: These MGAs do not imply any classification of quality, nor do they present a guarantee, given the complexity of the land in Barolo, that any specific MGA will express any terroir homogeneity – even if it is true the very concept does imply distinctive character. As such, neither the letters MGA nor the words “menzioni geografiche aggiuntive” have to appear on the label.

-

The DOCG zone of Barolo, which very approximately stretches about 15 kms north to south, from just below Alba, and just over 10 kms at its widest, encompasses 11 comunes, most of which, but not all, fall entirely within the zone. The comunes are;

Barolo

Castiglione Falletto,

Serralunga d’Alba,

Cherasco,

Diano d’Alba,

Grinzane Cavour,

La Morra,

Monforte d’Alba,

Novello,

Roddi

Verduno

-

In very general terms, we divide the Barolo zone by an imaginary line, running north to south, which notionally divides the western side, with its slightly softer and more generous wines, from the more ‘severe’, structured and powerful wines of the eastern portion. When it comes to Nebbiolo, of course, ‘softer’ is a rather relative term.

The overall soil makeup of the whole area is the famous blue-grey calcareous marl – in the west, somewhat more fertile and mixed with sand, while on the right-hand/eastern side, the lighter-coloured soils are less fertile and more interspersed with elements of limestone and clay. The other facets of ‘terroir’, like aspect, elevation and drainage eg, all make for an inexact science, but there are patterns of characteristics to the extent that an experienced taster can identify, and tasters either experienced or not, can enjoy subtle differences from place to place within this relatively small zone. We will expand on this in time.

-

It is also important to note that 11 of these MGAs are not Cru as such, but instead are comune recognitions, perhaps a bit like the Burgundian Villages Appellations, allowing for a composite wine from across the specific comune, as long as the components (or sole component) qualifies to be Barolo. So what we know as normale or Classico, just labelled Barolo (ie without a Cru identified) can be one of these MGAs and identified as Barolo del Comune di La Morra or Serralunga or any of those 11 comune names. But even if it’s drawn from a specific comune, the producer may just stick with labelling it as Barolo. This ‘base’ or ‘normale’ label can also indicate a wine drawn from either a single vineyard (Cru), but not identified as such, or from a combination of places across the whole Barolo zone.

-

Until fairly recently conventional wisdom has recognised 5 of these 11 as being the premier comunes of the zone; these are La Morra, Barolo, Monforte d’Alba, Castiglione Falletto and Serralunga d’Alba as they contain 140 of the 181 MGAs. Remembering that 11 of the MGAs cover the comunes it leaves just 31 of the recognised or Cru vineyards to be shared amongst the others (6 comunes). It’s now fair to say that another two communes join the hitherto elite 5. Novello and Verduno, which contain 18 Cru between them, and most importantly, the surely Grand Cru (another common-usage but completely unofficial term) vineyards of Ravera and Monvigliero, respectively, hardly need to do more to prove themselves. So between these 7 comunes they share the majority of Cru vineyards, and whatever number constitute the Grands Cru of Barolo More on this soon, too), they are all to be found in these 7 comunes.

-

Of course, only time will tell if the recent, fabulous 2016 or 2015 really are as great as legendary vintages ’82 or 1978, but whatever happens, they continue a pretty good run. Having tried plenty of wines from all vintages over the last couple of decades, I’d group them something like this – and happy to have some vintages in a couple of camps;

A handful of good wines made – 2002

Variable conditions, but plenty of good wines made – 2003, 2007, 2009, 2012, 2014, 2017

Very good vintages, some close to great, even if some underrated (like ’05, especially ’08) 2004, 2006, 2008, 2010, 2011 (especially on the eastern side), 2013, 2015 and definitely the elegant and misunderstood 2018.

Hard to argue against greatness – 2001, 2016. Might move 2004 up here yet.

Of other older vintages, and ones which you might occasionally come across, I’ve found ’99 to’96 inclusive, pretty reliable or better, and the 1990/’89 twinset, as usual, highly reliable to still present well.

2017s are clearly in need of good winemaking to control the warm conditions but show good aromatics and complexities overall. 2018 introductory level wines , like Langhe and Nebb d’Alba, have generally shown superbly and my extensive tastings in January ‘22 confirm wines of great elegance but also ample weight – in fact, many truly beautiful wines. 2019 will be unarguably fine to great, 2020 also, while ’21 can be called already; spectacular, no doubt.